Category: Hitachi

Sega Saturn

This is my Sega Saturn, which I bought used at The Record Exchange (now simply The Exchange) on Howe Rd. in Cuyahoga Falls in October 1999.

I know this because I saved the date-stamped price tag by sticking it on the Saturn’s battery door.

The Saturn was Sega’s 32-bit game console, a contemporary of the better known Nintendo N64 and the Sony PlayStation. It lived a short, brutish existence where it was pummeled by the PlayStation. In the US the Saturn came out in May 1995 and was basically dead by the end of 1998.

The Saturn was the first game console that I truly loved. Keep in mind that I bought mine after the platform was dead and buried and used game stores were eager to unload most of the games for less than $20. If I had paid $399 for one brand new in 1995 with a $50 copy of Daytona USA I might have different feelings.

The thing that makes the Saturn intensely interesting is how it was simultaneously such a lovable platform and a disaster for Sega. It’s a story about what happens when executives totally misunderstand their market and what happens when you give great developers a limited canvas to make great games with and they do the best they can.

When you look at the Saturn totally out of it’s historical context and just look at on it’s own, it’s a fine piece of gaming hardware. Compared to the Sega CD it replaced the quality of the plastic seems to have been improved. The Saturn is substantial without being outrageously huge. The whole thing was built around a top-loading 2X CD-ROM drive.

It plays audio CDs from an on-screen menu that also supports CD+G discs (mostly for karaoke).

It has a CR2032 battery that backs up internally memory for saving games, accessible behind a door at the rear of the console.

It has a cartridge slot for adding additional RAM and other accessories like GameSharks.

There were several official controllers available for it during it’s lifetime.

The two I own are the this 6 button digital controller:

And the “3D controller” with the analog stick that was packaged with NiGHTS:

You can see the clear family resemblance to the Dreamcast controller.

My Saturn is a bit odd because at some point the screws that hold the top shell to the rest of the console sheared off.

That’s not supposed to happen. All that’s holding the two parts of the Saturn together is the clip on the battery door. Fortunately this gives me an excellent opportunity to show you what the inside of the Saturn looks like:

Despite all of this, my Saturn still works after at least 15 years of service.

I should explain why I was buying a Saturn for $25 at The Record Exchange in 1999. You might say that several decisions by my parents and misguided Sega executives led to that moment.

My parents never bought my brother and I videogames as children. I’m not sure if they thought games were time wasters or wastes of money. Or, it could have just been they didn’t have any philosophical problem with them but they were uncomfortable buying a toy more expensive than $100. Whatever the reason we didn’t have videogames. Considering how many awful games people dropped $50 on in the pre-Internet days when there was so little information about which games were worth buying, I can see their point. I also know now that there were plenty of perfectly good games that were so difficult that you might stop playing in frustration and never get your money’s worth out of them.

Instead, videogames were something I would only see at a friend’s house…and when those moments happened they were magical.

I can’t speak for women of my generation but at least for a lot of males of the so-called “Millennial generation” videogames are to us what Rock ‘n Roll was to the Baby Boomers. They are the cultural innovation that we were the first to grow up with and they define us as a generation. If you’re looking for particular images that define a generation and I say to you “Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock” you think Baby Boomers. If I say to you “Super Mario Bros.” you think Millennials.

By 1996 or so I was pretty interested in buying some sort of videogame console, but I was somewhat restricted in what I could afford. The first game system I bought was a used original Game Boy in 1996. However, shortly after that my family got a current PC and my interests shifted to computer games: Doom, Quake, etc, which is what eventually led to the Voodoo 2.

By 1998 I noticed how dirt cheap the Sega Genesis had become so my brother and I chipped in together to buy a used Genesis (which I believe we bought from The Record Exchange). I quickly found that I did enjoy playing 2D games but I was really enjoying the 3D games I was playing on PC.

Sega did an oddly consistent job of porting their console games to PC in the 1990s, so I had played PC versions of some of the games that came out on Saturn in the 1995-1998 timeframe including the somewhat middling PC port of Daytona USA

So in 1999 when I came across this used Saturn for a mere $25 at The Record Exchange, I was eager to buy it.

But why was the Saturn $25 when a used PlayStation or N64 was most likely going for $80-$100 at the same time?

As I noted in the Sega Genesis Nomad post, Sega was making some very strange decisions about hardware in the mid-1990s. At that time Sega was at at the forefront of arcade game technology. Recall that in the Voodoo 2 post I said that if you sat down at one of Sega’s Daytona USA or Virtua Fighter 2 machines in 1995 you were basically treated to the most gorgeous videogame experience money could by at the time. That’s because Sega was working with Lockheed Martin to use 3D graphics hardware from flight simulators in arcade machines.

At the same time as they were redefining arcade games Sega was busy designing the home console that would succeed the popular Genesis (aka the console people refer to today as simply “the Sega”). Home consoles were still firmly rooted in 2D, but there were cracks appearing. For example, Nintendo’s Star Fox for the Super Nintendo embedded a primitive 3D graphics chip in the cartridge and introduced a lot of home console gamers to 3D, one slowly rendered frame at a time. Sega pulled a similar trick with the Genesis port of Virtua Racing, which embedded a special DSP chip in the cartridge (you may remember this from the Nomad post):

Sega decided on a design for the Saturn which would produce excellent 2D graphics with 3D graphics as a secondary capability. The way the Saturn produced 3D was a bit complicated but basically it could take a sprite and position it in 3D space in such a way that it acted like a polygon in 3D graphics. If you place enough of these sprites on the screen you can create a whole 3D scene.

I can see in retrospect how this made sense to Sega’s executives. People like 2D games, so let’s make a great 2D machine. They also must have considered that 3D hardware on the same level as their arcade hardware was not feasible in a $400 home console.

However, Sega’s competitors didn’t see things that way. Sony and Nintendo both built the best 3D machines they could, 2D be damned. One would expect their did this largely in response to the popularity of Sega’s 3D arcade games.

The story that’s gone around about Sega’s reaction to this is that in response they decided to put a second CPU in the Saturn. I have no idea if that’s why the Saturn ended up with two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs, but it would make sense if was an act of desperation.

Having two CPUs is one of those things that sounds great but in reality can turn into a real mess. A CPU is only as fast as the rest of the machine can feed it things to do. If say, one CPU is reading from the RAM and the other can’t at the same time, it sits there idle, waiting. There are also not that many kinds types of work that can easily be spread across two CPUs without some loss in efficiency. If the work one CPU is doing depends on work the other CPU is still working on the first CPU sits there idle, waiting. These are problems in computer science that people are still working furiously on today. These were not problems Sega was going to solve for a rushed videogame console launch 19 years ago.

The design they ended up with for the Saturn was immensely complicated. All told, it contained:

- Two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs

- One graphics processor for sprites and polygons (VDP1)

- One graphics processor for background scrolling (VDP2)

- One Hitachi SH-1 CPU for CD-ROM I/O processing

- One Motorola 68000 derived CPU as the sound controller

- One Yamaha FH1 sound DSP

- Apparently there was another custom DSP chip to assist for 3D geometry processing

That’s a lot of silicon. It was expensive to manufacturer and difficult to program. The PlayStation, which started life at $299, had a single CPU and a single graphics processor and in general produced better results than the Saturn.

Sega had psyched itself out. Here the company that was showing everyone what brilliant 3D arcade games looked like failed to understand that they had actually fundamentally changed consumer expectations and built a game console to win the last war, so to speak.

When the PlayStation and N64 arrived they ushered in games that were built around 3D graphics. Super Mario 64, in particular made consumers expect increasingly rich 3D worlds, exactly the type of thing the Saturn did not excel at.

Sega had gambled on consumers being interested in the types of games they produced for the arcades: Games that were short but required hours of practice to master. By 1997-1998 consumers’ tastes had changed and they were enjoying games like Gran Turismo that still required hours to master but offered hours of content as well. 1995’s Sega Rally only contained four tracks and three cars. 1998’s Gran Turismo had 178 cars on 11 tracks.

Sega’s development teams eventually adapted to this new reality but it was too late to save the doomed Saturn. Brilliant end-stage Saturn games like Panzer Dragoon Saga and Burning Rangers would never reach enough players’ hands to make a difference.

For the eagle eyed…This is a US copy of Burning Rangers with a jewel case insert printed from a scan of the Japanese box art.

By Fall-1999 the Saturn was dead and buried as a game platform. Not only had it failed in the marketplace but it’s hurried successor, the Dreamcast, was now on store shelves. That’s why a used Saturn was $25 in 1999.

The thing was that despite the fact that the Saturn had failed, the games weren’t bad, and since I was buying them after the fact they were dirt cheap. I accumulated quite a few of them:

Oddly enough, my favorite Saturn game was the much criticized Saturn version of Daytona USA that launched with the Saturn in 1995.

The original Saturn version of Daytona USA was a mess. Sega’s AM2 team, who had developed the original arcade game had been tasked with somehow creating a viable Saturn version of Daytona USA. The whole point of the game was that you were racing against a large number of opponents (up to 40 on one track). The Saturn could barely do 3D and here it was being asked to do the impossible.

The game they produced was clearly a rushed, sloppy mess. But it was still fun! The way the car controls is still brilliant even if the graphics can barely keep up. I fell in love with Daytona. Later Sega attempted several other versions of Daytona on Saturn and Dreamcast but I vastly prefer the original Saturn version, imperfect as it may be.

Another memorable game was Wipeout. To be honest, when I asked to see what Wipeout was one day at Funcoland I had no idea that the game was a futuristic racing game. I thought it had something to do with snowboarding!

Wipeout was a revelation. Sega’s games were bright and colorful with similarly cheerful, jazzy music. Wipeout is a dark and foreboding combat racing game that takes place in a cyberpunk-ish corporate dominated future. I still catch myself humming the game’s European electronica soundtrack. The game used CD audio for the soundtrack so you could put the disc in a CD player and listen to the music separately if you wished. Wipeout was the best of what videogames had to offer in 1995: astonishing 3D visuals and CD quality sound.

From about 1999 to 2000 I had an immense amount of fun collecting cheap used Saturn classics like NiGHTS, Virtua Cop, Panzer Dragoon, Sonic R, Virtua Fighter 2, Sega Rally, and others…As odd as this is to say, the Saturn was my console videogame alma mater.

Today I understand that something can be a business failure but not a failure to the people who enjoyed it. To me, the Saturn was a glorious success and I treasure the time I have had with it.

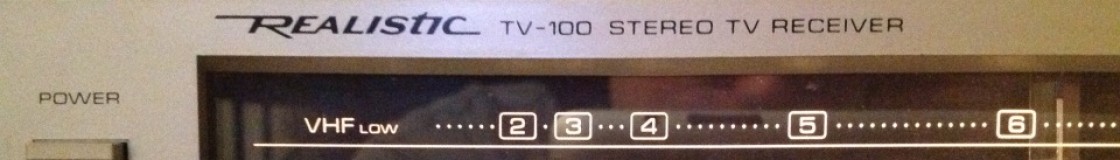

Realistic CD-1000

This is the Realistic CD-1000 CD player that I found just this past Tuesday at Village Thrift.

This is the first time I’ve found an item and posted it to the blog in the same week. When I saw this in the electronics section at Village Thrift I could tell it was pretty old from the styling, but when I saw the August 1984 manufacture date I knew I had something really special on my hands.

Checking the 1985 Radio Shack catalog confirmed what I suspected: The CD-1000 is the very first CD player that Radio Shack sold. Given my already discussed fondness for Radio Shack and Realistic I had to have it.

The problem was that the price was marked “3.00 As Is”. If Village says something is as-is, most likely it plain doesn’t work. But, for $3, I’m willing to take a chance.

When I got it home it became apparent what the problem was: While the player would turn on, the CD drawer refused to open.

I opened up the case to see if I could spot anything obviously amiss inside. The first thing I noticed was that there was a CD-R disc that must have been stuck inside the machine when it was donated that had slipped out of the drawer and was sitting among the electronics. After removing the CD-R I tried watching the CD drawer try to open with the case open. All I heard was a motor try to turn but nothing moved.

Next, I took it to my father. He quickly discovered that the belt that goes between a motor and that white, round piece in the bottom center of the picture above was broken.

We then proceeded to remove the drawer assembly from the unit to get a better look. That involved unplugging all of the connections between the drawer and the main board.

Eventually we got the drawer assembly out of the unit. My father manually turned the round white piece and we discovered how the drawer works. As you would expect, first the drawer pulls in. What was really curious was seeing the little platform on the center of the drawer move.

See that raised platform where you place the disc? It works like an elevator that places the disc onto the drive spindle. Then the white plastic piece with the “Danger!…” sticker on it moves downward and clamps the disc in place. All of this was driven by that single white round piece with the broken belt.

The next day, my father took the drive assembly to Philcap Electronics where they took some measurements and sold him a replacement belt for $3.

After he installed the new belt and reconnected all of the wires the CD player worked! I’m personally somewhat shocked that nothing else was broken on this thing but that belt. In researching this unit you find people talking about problems with distorted sound and the laser failing, but my player seems to work perfectly after the belt repair.

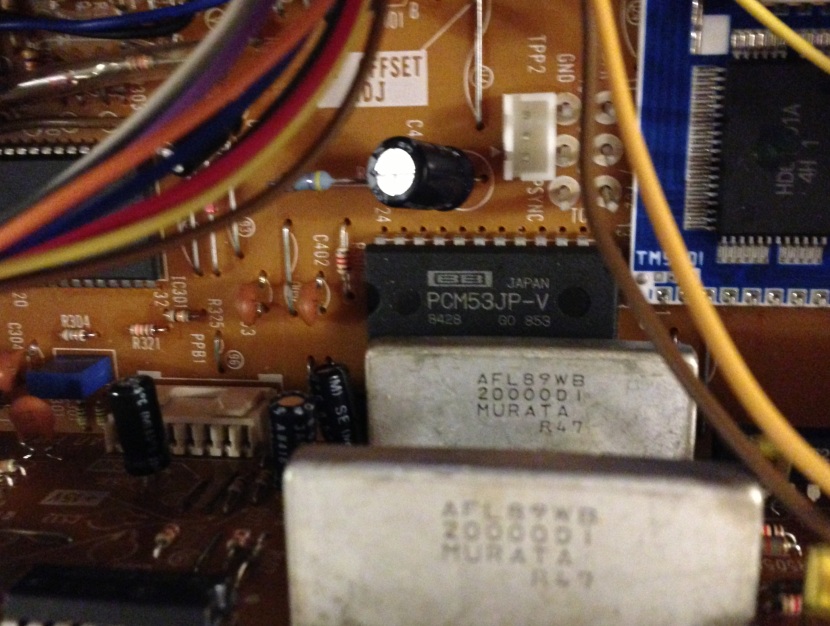

The thing about CD players that is a blessing and a curse is that to a close approximation they basically all sound the same. I had heard though, that the very earliest CD players had some nasty filtering in their early DACs that might be audible. Personally, it sounded to great to my ears. That got me curious about what all of those chips were inside the CD-1000.

The first thing I found was that this player was probably designed for Tandy by Hitachi. Most of the chips inside are Hitachi chips. I stumbled upon this French website about another, much more flashy early CD player, the Hitachi DA-1000 that shows the chips it had inside of it.

Notice that both players used the MB15529 chip. Those two other chips next to it also look similar. The description of those chips is in French, but Google Translate tells me that the MB15529 decodes the bitstream into frames and the HD60901H does error conversion. Basically, these chips are the digital portion after the drive reads the bits and before the DAC turns them into analog sound.

The DAC used in the Realistic player is a 16-bit Burr Brown PCM53JP-V DAC.

It sounds like this was a common chip in pro audio equipment in the 1980s. It also looks like they’re even still in demand today to repair old gear. The Burr Brown DAC is probably why this unit sounds so good today.

From what I can gather the first generation of CD players like the famous Sony CDP-101 was from 1982-1983. By 1984-1985 when my CD-1000 debuted the hardware was settling down a bit.

This raises an interesting point about the CD-1000. Even at the time, this was an austere player. The design was pretty low-key compared to something like that over-the-top Hitachi DA-1000 I linked to above. The CD-1000 had no headphone input, no remote control, and a basic (but beautiful) display. On the other hand, the CD-1000 debuted at $400 which was probably more affordable than most players at the time. And yet, Radio Shack and Hitachi did not skimp on components, since the guts look comparable to the DA-1000.

It’s interesting to see how the designers of the CD-1000 dealt with things that are commonplace today. For example, there is no next track button. What you do instead is hold play and press the fast forward or rewind button to skip a track. If you just hit the fast forward or rewind buttons it seeks rather than skipping. If you want to skip to track 12 you have to hit the 1 button, then the 2 button, and then press Play.

The display is a simple affair with lovely, bright florescent digits.

Listening to a CD player for the first time in 1984 must have been amazing. The 1980s were a time of electronic novelties. There were portable TVs, personal computers, various type of home video like Beta, VHS and LaserDisc, huge early cellular phones, etc. But, none of them could hold a candle to the shockingly great sound of a Compact Disc. No pops, no scratches, no tape hiss. Just clean sound with amazing dynamic range. Some of the pro-CD propaganda from that era was nonsense, such as how the discs were indestructible, but the promise of clean sound was true. The Compact Disc was the ultimate 1980s novelty.

Today, as people re-embrace vinyl we forget the lesson the CD player taught us: Analog is tyranny. That is to say that in analog audio there’s always some noise, always some distortion and all you can do is spend more money to minimize it. That’s awful, when you think about it. You can whine all you want about the loveliness of analog audio but what it meant was that a select few who could afford expensive hi-fi systems got to listen to great sound and everyone else got less than that. Yes, you can have a great record player that minimizes surface noise and produces spine-tingling sound, but if you can’t make it affordable and give it to the masses, what’s the point of that?

So, if you walked into a Radio Shack in late 1984 and were blown away listening to a CD-1000 for the first time you were hearing not a $5000 turntable but a $400 component you were much more likely to be able to afford.

I can appreciate that album artwork looks much, much better on an LP dust jacket. Fundamentally I think that’s why vinyl is coming back into fashion now. It’s the beautiful artwork. There’s also a readily understandable beauty to watching a vinyl disc spin with music coming out.

But we too often forget the beauty of digital audio. It wasn’t until I watched this fantastic video from Xiph.org (YouTube link if your browser doesn’t support WebM) about the common misconceptions about how digital audio works that I realized how fortunate we are to have had the CD and 16-bit/44.1KHz PCM digital audio. The most surprising thing about the video is how Monty explains that human ears don’t really need anything better than 16/44 because 16/44 can reproduce any frequency we can hear. I had always assumed that more bits and more samples would mean better audio, but that’s not the case. Given two sampled points at a 44.1KHz sample rate there is only a single waveform that fits those points that is within the range of human hearing. The 16-bit sample depth already produces a dynamic range that exceeds the range of our ear’s sensitivity and a noise floor that is inaudible. We will never need anything greater than 16/44 with the speaker technology we possess today and the ears we will always possess.

The compact disc was unwittingly the last physical consumer electronics audio format. The depth of the 16/44 format meant that there will never be another format that sounds better to most people. For playback, there’s no need to go further.

More importantly though, by pressing hundreds of millions of discs full of unencrypted 16/44 PCM, the industry laid the groundwork for the future. Bits are inherently portable. Get those bits off of the CD and they can go anywhere and be physically stored in a drive of any size.

What’s killing the CD now is the tyranny of space. Storing discs takes up space. Players take up space. With digital the beauty is that the music is in the bits, and not the physical medium (which is how digital defeated analog in the first place). You can make digital storage basically as small as you want. But the polycarbonate disc never matter in the first place. What mattered are the bits. And they are likely to live forever.