Category: Nintendo

Sega Saturn

This is my Sega Saturn, which I bought used at The Record Exchange (now simply The Exchange) on Howe Rd. in Cuyahoga Falls in October 1999.

I know this because I saved the date-stamped price tag by sticking it on the Saturn’s battery door.

The Saturn was Sega’s 32-bit game console, a contemporary of the better known Nintendo N64 and the Sony PlayStation. It lived a short, brutish existence where it was pummeled by the PlayStation. In the US the Saturn came out in May 1995 and was basically dead by the end of 1998.

The Saturn was the first game console that I truly loved. Keep in mind that I bought mine after the platform was dead and buried and used game stores were eager to unload most of the games for less than $20. If I had paid $399 for one brand new in 1995 with a $50 copy of Daytona USA I might have different feelings.

The thing that makes the Saturn intensely interesting is how it was simultaneously such a lovable platform and a disaster for Sega. It’s a story about what happens when executives totally misunderstand their market and what happens when you give great developers a limited canvas to make great games with and they do the best they can.

When you look at the Saturn totally out of it’s historical context and just look at on it’s own, it’s a fine piece of gaming hardware. Compared to the Sega CD it replaced the quality of the plastic seems to have been improved. The Saturn is substantial without being outrageously huge. The whole thing was built around a top-loading 2X CD-ROM drive.

It plays audio CDs from an on-screen menu that also supports CD+G discs (mostly for karaoke).

It has a CR2032 battery that backs up internally memory for saving games, accessible behind a door at the rear of the console.

It has a cartridge slot for adding additional RAM and other accessories like GameSharks.

There were several official controllers available for it during it’s lifetime.

The two I own are the this 6 button digital controller:

And the “3D controller” with the analog stick that was packaged with NiGHTS:

You can see the clear family resemblance to the Dreamcast controller.

My Saturn is a bit odd because at some point the screws that hold the top shell to the rest of the console sheared off.

That’s not supposed to happen. All that’s holding the two parts of the Saturn together is the clip on the battery door. Fortunately this gives me an excellent opportunity to show you what the inside of the Saturn looks like:

Despite all of this, my Saturn still works after at least 15 years of service.

I should explain why I was buying a Saturn for $25 at The Record Exchange in 1999. You might say that several decisions by my parents and misguided Sega executives led to that moment.

My parents never bought my brother and I videogames as children. I’m not sure if they thought games were time wasters or wastes of money. Or, it could have just been they didn’t have any philosophical problem with them but they were uncomfortable buying a toy more expensive than $100. Whatever the reason we didn’t have videogames. Considering how many awful games people dropped $50 on in the pre-Internet days when there was so little information about which games were worth buying, I can see their point. I also know now that there were plenty of perfectly good games that were so difficult that you might stop playing in frustration and never get your money’s worth out of them.

Instead, videogames were something I would only see at a friend’s house…and when those moments happened they were magical.

I can’t speak for women of my generation but at least for a lot of males of the so-called “Millennial generation” videogames are to us what Rock ‘n Roll was to the Baby Boomers. They are the cultural innovation that we were the first to grow up with and they define us as a generation. If you’re looking for particular images that define a generation and I say to you “Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock” you think Baby Boomers. If I say to you “Super Mario Bros.” you think Millennials.

By 1996 or so I was pretty interested in buying some sort of videogame console, but I was somewhat restricted in what I could afford. The first game system I bought was a used original Game Boy in 1996. However, shortly after that my family got a current PC and my interests shifted to computer games: Doom, Quake, etc, which is what eventually led to the Voodoo 2.

By 1998 I noticed how dirt cheap the Sega Genesis had become so my brother and I chipped in together to buy a used Genesis (which I believe we bought from The Record Exchange). I quickly found that I did enjoy playing 2D games but I was really enjoying the 3D games I was playing on PC.

Sega did an oddly consistent job of porting their console games to PC in the 1990s, so I had played PC versions of some of the games that came out on Saturn in the 1995-1998 timeframe including the somewhat middling PC port of Daytona USA

So in 1999 when I came across this used Saturn for a mere $25 at The Record Exchange, I was eager to buy it.

But why was the Saturn $25 when a used PlayStation or N64 was most likely going for $80-$100 at the same time?

As I noted in the Sega Genesis Nomad post, Sega was making some very strange decisions about hardware in the mid-1990s. At that time Sega was at at the forefront of arcade game technology. Recall that in the Voodoo 2 post I said that if you sat down at one of Sega’s Daytona USA or Virtua Fighter 2 machines in 1995 you were basically treated to the most gorgeous videogame experience money could by at the time. That’s because Sega was working with Lockheed Martin to use 3D graphics hardware from flight simulators in arcade machines.

At the same time as they were redefining arcade games Sega was busy designing the home console that would succeed the popular Genesis (aka the console people refer to today as simply “the Sega”). Home consoles were still firmly rooted in 2D, but there were cracks appearing. For example, Nintendo’s Star Fox for the Super Nintendo embedded a primitive 3D graphics chip in the cartridge and introduced a lot of home console gamers to 3D, one slowly rendered frame at a time. Sega pulled a similar trick with the Genesis port of Virtua Racing, which embedded a special DSP chip in the cartridge (you may remember this from the Nomad post):

Sega decided on a design for the Saturn which would produce excellent 2D graphics with 3D graphics as a secondary capability. The way the Saturn produced 3D was a bit complicated but basically it could take a sprite and position it in 3D space in such a way that it acted like a polygon in 3D graphics. If you place enough of these sprites on the screen you can create a whole 3D scene.

I can see in retrospect how this made sense to Sega’s executives. People like 2D games, so let’s make a great 2D machine. They also must have considered that 3D hardware on the same level as their arcade hardware was not feasible in a $400 home console.

However, Sega’s competitors didn’t see things that way. Sony and Nintendo both built the best 3D machines they could, 2D be damned. One would expect their did this largely in response to the popularity of Sega’s 3D arcade games.

The story that’s gone around about Sega’s reaction to this is that in response they decided to put a second CPU in the Saturn. I have no idea if that’s why the Saturn ended up with two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs, but it would make sense if was an act of desperation.

Having two CPUs is one of those things that sounds great but in reality can turn into a real mess. A CPU is only as fast as the rest of the machine can feed it things to do. If say, one CPU is reading from the RAM and the other can’t at the same time, it sits there idle, waiting. There are also not that many kinds types of work that can easily be spread across two CPUs without some loss in efficiency. If the work one CPU is doing depends on work the other CPU is still working on the first CPU sits there idle, waiting. These are problems in computer science that people are still working furiously on today. These were not problems Sega was going to solve for a rushed videogame console launch 19 years ago.

The design they ended up with for the Saturn was immensely complicated. All told, it contained:

- Two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs

- One graphics processor for sprites and polygons (VDP1)

- One graphics processor for background scrolling (VDP2)

- One Hitachi SH-1 CPU for CD-ROM I/O processing

- One Motorola 68000 derived CPU as the sound controller

- One Yamaha FH1 sound DSP

- Apparently there was another custom DSP chip to assist for 3D geometry processing

That’s a lot of silicon. It was expensive to manufacturer and difficult to program. The PlayStation, which started life at $299, had a single CPU and a single graphics processor and in general produced better results than the Saturn.

Sega had psyched itself out. Here the company that was showing everyone what brilliant 3D arcade games looked like failed to understand that they had actually fundamentally changed consumer expectations and built a game console to win the last war, so to speak.

When the PlayStation and N64 arrived they ushered in games that were built around 3D graphics. Super Mario 64, in particular made consumers expect increasingly rich 3D worlds, exactly the type of thing the Saturn did not excel at.

Sega had gambled on consumers being interested in the types of games they produced for the arcades: Games that were short but required hours of practice to master. By 1997-1998 consumers’ tastes had changed and they were enjoying games like Gran Turismo that still required hours to master but offered hours of content as well. 1995’s Sega Rally only contained four tracks and three cars. 1998’s Gran Turismo had 178 cars on 11 tracks.

Sega’s development teams eventually adapted to this new reality but it was too late to save the doomed Saturn. Brilliant end-stage Saturn games like Panzer Dragoon Saga and Burning Rangers would never reach enough players’ hands to make a difference.

For the eagle eyed…This is a US copy of Burning Rangers with a jewel case insert printed from a scan of the Japanese box art.

By Fall-1999 the Saturn was dead and buried as a game platform. Not only had it failed in the marketplace but it’s hurried successor, the Dreamcast, was now on store shelves. That’s why a used Saturn was $25 in 1999.

The thing was that despite the fact that the Saturn had failed, the games weren’t bad, and since I was buying them after the fact they were dirt cheap. I accumulated quite a few of them:

Oddly enough, my favorite Saturn game was the much criticized Saturn version of Daytona USA that launched with the Saturn in 1995.

The original Saturn version of Daytona USA was a mess. Sega’s AM2 team, who had developed the original arcade game had been tasked with somehow creating a viable Saturn version of Daytona USA. The whole point of the game was that you were racing against a large number of opponents (up to 40 on one track). The Saturn could barely do 3D and here it was being asked to do the impossible.

The game they produced was clearly a rushed, sloppy mess. But it was still fun! The way the car controls is still brilliant even if the graphics can barely keep up. I fell in love with Daytona. Later Sega attempted several other versions of Daytona on Saturn and Dreamcast but I vastly prefer the original Saturn version, imperfect as it may be.

Another memorable game was Wipeout. To be honest, when I asked to see what Wipeout was one day at Funcoland I had no idea that the game was a futuristic racing game. I thought it had something to do with snowboarding!

Wipeout was a revelation. Sega’s games were bright and colorful with similarly cheerful, jazzy music. Wipeout is a dark and foreboding combat racing game that takes place in a cyberpunk-ish corporate dominated future. I still catch myself humming the game’s European electronica soundtrack. The game used CD audio for the soundtrack so you could put the disc in a CD player and listen to the music separately if you wished. Wipeout was the best of what videogames had to offer in 1995: astonishing 3D visuals and CD quality sound.

From about 1999 to 2000 I had an immense amount of fun collecting cheap used Saturn classics like NiGHTS, Virtua Cop, Panzer Dragoon, Sonic R, Virtua Fighter 2, Sega Rally, and others…As odd as this is to say, the Saturn was my console videogame alma mater.

Today I understand that something can be a business failure but not a failure to the people who enjoyed it. To me, the Saturn was a glorious success and I treasure the time I have had with it.

Nintendo Game Boy Micro

I had originally planned to put up a different post this week but some technical issues and the fact that I had a cold means that post will have to wait for some other week.

Today though, I’m going to bend the rules somewhat because this is an item that technically I didn’t buy at a thrift store but I did buy used.

This is my Nintendo Game Boy Micro which I purchased sometime in 2008 at The Exchange in Cuyahoga Falls.

Released in 2005, the Game Boy Micro is a miniaturized Game Boy Advance that loses compatibility with original Game Boy and Game Boy Color games but gained a brilliant (if tiny) screen and a headphone jack that the Game Boy Advance SP oddly lacked..

The Game Boy Micro is, in my opinion, the sexiest piece of videogame hardware ever created. It’s so tiny and jewel-like while at the same time so utterly minimalistic that it just looks better than anything else Nintendo, or perhaps anyone making portable game systems has ever made. It’s not surprising looking at it’s brushed metal construction that the Micro was a contemporary of the iPod Mini and was widely believed to be Nintendo’s bid to capture customers looking for another stylish portable gizmo. It’s so beautiful that you almost feel bad inserting a cartridge because it clashes with the color scheme.

Practially the Micro can be a bit tough to hold for any long period of time. The tiny size (it only measures 50×101×17.2 mm) means that in order to have your index fingers on the shoulder buttons and your thumbs on the D-pad and a+b buttons there’s a good chance you’ll have to hold your hands at an uncomfortable angle. I have pretty small hands and holding the Micro is just about at the edge of discomfort for me. Additionally, while the screen is bright and the colors are well defined the screen is still just 2 inches wide.

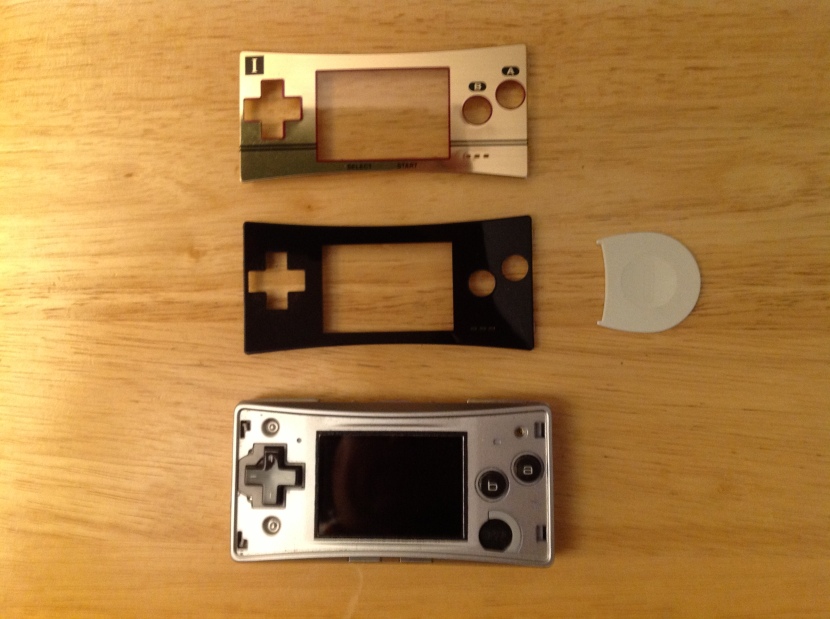

The Micro’s party piece is that it’s faceplates are removable so you can change the appearance of the system by changing faceplates with a plastic tool.

Here are the three faceplates I own, along with the plastic tool:

I believe that when I bought the Micro used it was wearing the obnoxious red/orange faceplate. Back in 2008 you could still order new faceplates from Nintendo’s parts site so I bought the stylish black plate and the nostalgic Famicom faceplate. Sadly today they only offer replacement AC-adaptors.

The plastic tool inserts into these two holes on the side of the Micro with the D-pad (on either side of the screw):

Micro owner Pro-tip: Always insert new faceplates so that you hook in the side with the longer hooks near the a+b buttons first.

This is what the Micro looks like without any faceplate mounted:

One practical advantage to the faceplates is that they act as hard screen protectors, but really they just look bitch’n cool.

However, the real reason I want to talk about the Game Boy Micro is it’s historical significance to Nintendo. The Game Boy Micro is the last Game Boy as well as the last 2D gaming system from Nintendo.

Now, I would not be shocked if some day Nintendo reuses the Game Boy name but suffice to say Nintendo started selling a line of cartridge-based portable game systems with four face buttons (labeled a, b, start, and select), a D-pad, and one screen in 1989 with the original Game Boy and created a succession of systems with those attributes that ended in 2005 with the Game Boy Micro.

Following the Game Boy Micro Nintendo retired the Game Boy name and has produced the Nintendo DS line of cartridge-based portable game systems with two screens, one of which is a stylus-based resistive touchscreen, six face buttons (labeled a, b, x, y, start, and select), and (at least) a D-pad.

More importantly though, the Game Boy Micro was the last Nintendo system of any kind that was primarily built to play games based on 2D, sprite-based graphics rather than today’s 3D, polygon-based graphics.

This means that the Game Boy Micro was Nintendo’s final love letter to the era when it dominated the videogame world with the NES/Famicom and SuperNES/Super Famicom. There’s no coincidence to the fact that the Micro itself resembles and NES/Famicom controller.

From the release of the Famicom in 1983 to December 3rd, 1994 (when Sony released the Playstation in Japan) Nintendo was undoubtedly the single most important force in the console videogame world. Surely Sega played some part as well, but while they could on occasion be Nintendo’s equal they were never Nintendo’s superior.

But, as the world marveled at the Playstation and the rise of 3D graphics, Nintendo’s influence crested and then began to wane. Today they are an important part of the industry, but they have never again become undisputed champion.

However, in the portable gaming arena, Nintendo was still the undisputed champion (and still is today, as tough as it is for this PSP and Vita owner to admit). When Nintendo decided to replace the Game Boy Color in 2001 it returned to a 2D-based system and created the Game Boy Advance. An era of 2D nostalgia reigned with the GBA finding itself home to classics of the 16-bit era re-released as GBA games and new 2D classics that heavily drew inspiration from SNES games.

So, when Nintendo said it’s final goodbye in 2005 with the Game Boy Micro it was really closing the door on the era of 2D gaming it had dominated from 1983 to 2005. In that way the Micro is comparable to the last tube-based Zenith Transoceanic or the last piston-engined Grumman fighter aircraft. When a great company wants to say goodbye to one of it’s great products they will often create something fantastic as a last hurrah and that is clearly what Nintendo did with the Game Boy Micro.