Category: Games

A Meditation on Racing Videogames

I’ve been on a videogame kick recently, so I ask if you will indulge me once again. The post on the Saturn, and my memories of Daytona USA and Wipeout specifically, stirred my thoughts about the racing game genre.

I own a few racing videogames.

It hadn’t actually occurred to me quite how many racing games I own until I tried to gather most of them in one place to get this picture. I also have several groups of games not shown here:

- A whole era of PC racing games from 1997-2005 or so like Rally Trophy, Motorhead, Rallisport Challenege, Colin McRae 3, and others I don’t have the boxes for at my apartment.

- A whole group of PC racing games like Midtown Madness that I just have in jewel cases from thrift stores.

- More recent purchases like Dirt 2, Blur, Fuel, and Grid 2 that I only own digitally.

I’m not really a big car guy or even someone who really enjoys driving in real life. It’s not really the cars that draw me into racing games.

I think what it comes down to is that I love playing videogames but I hate the “instant death” mechanic in most types of games.

That is to say that if Mario falls down a hole, he’s dead and you have to go back to the start of the level. If a Cyber Demon’s rocket hits Doom Guy he’s dead and you go back to the start to the level. In the vast majority of games the punishment for failure is that you the player are ripped away from whatever you’re doing and you lose progress in some way.

Racing games are in many ways the opposite of this. If you go off the road or hit a wall generally you lose time and you’ll probably not win the race, but the the priority is to politely get you going on your way again. Even in games like San Francisco Rush, where you can hit a wall and explode, you are quickly thrust back into the race somewhere further down the track. It’s like if you spilled a glass of water at a nice restaurant and the waiter quickly comes over to mop it up and replace your drink. You and he both know you just did a silly thing but he wants you back enjoying yourself as soon as possible.

That does not mean that these games are “soft”; it’s just that they don’t believe that constantly slapping you across the face is good value for money.

I mentioned in the Sega Saturn post that I don’t tend to like 2D games. The vast majority of racing games operate from an inherently 3D perspective that places the camera either behind the car or on the car’s bumper. In the pre-3D era there were attempts to do racing games with 3D-ish perspectives using 2D graphics, and I own a few such as Pole Position II, and Outrun.

It was difficult for 2D games to draw a convincing curving road so these games tend to make the player avoid traffic rather than attempt to portray realistic driving.

Racing games as we know them today trace their ancestry back to arcade games like Namco’s Winning Run (1988) and Sega’s Virtua Racing (1992) that were among the first to use 3D graphics and be able to draw a road in a more realistic way.

When consoles started using 3D graphics a nice looking racing game was a surefire way for console makers to show off their technology. A nicely rendered car on some nicely rendered road with some glittering buildings behind it is much less likely to trigger the uncanny valley than a rendering of a human. I think we can all agree that games like Gran Turismo 5 have come closer to real looking car paint than any game has come to real looking human skin.

Throughout the 1990s racing games exploded into several distinct sub-genres:

Arcade style games are the direct descendants of Virtua Racing and Winning Run, which is where the sub-genre derives it’s name. These days, these games are seldom released in arcades. Arcade-style racing games are not expected to have realistic handling but instead have handling designed for fun more than thought. The brake peddle/button in many of these games is a mere formality. Early on in the 3D racing era companies like Namco and Sega added drift mechanics to their games where you could toss the car around corners at speed rather than braking realistically. Arcade racers like Daytona USA and Ridge Racer were very popular in the 32-bit era (Playstation, N64, Saturn) but the arrival of mainstream simulation racers drew attention away from these games in the late 1990s and early 2000s (which sadly meant many people overlooked the fantastic Ridge Racer Type 4). The arrival of Burnout 3: Takedown in 2004 reinvigorated the sub-genre by allowing you to knock other cars off the road rather than just trying to pass them.

Beginning with games like Driver, free-roaming racing games left the predefined track and let the player roam though cities and other environments. Crazy Taxi (1999) combined the arcade-style with free-roaming forcing the player to memorize routes through a large city in order to pick up and deliver fares. Test Drive Unlimited (2006) allowed players to drive around the whole island of Oahu. Burnout Paradise (2008) put the frantic Burnout style of arcade racing into an open city.

Kart racing games (named after Super Mario Kart) tend to have arcade style handling but in most cases have a recognized character like Mario or Sonic sitting in a tiny car. In Kart racers it’s expected that you can driver over or through symbols/objects on the track to pick up weapons, which you can use to slow down or otherwise befuddle opponents, or drive over speed pads which give you a nitro boost. In Kart games the strategy of using the weapons is as important or more important than your ability to guide the car. The Kart racing genre is 90% Mario Kart and 10% everyone else. If you’ve never played them, I recommend Sega’s two recent kart racing games: Sonic and Sega All-Stars Racing and it’s sequel Sonic & All-Stars Racing Transformed.

Futuristic racing games are a close cousin to Kart racers because they also allow you to pick up weapons on the track to hurt opponents. Generally futuristic racing games have more realistic graphics than Kart games and a cyberpunk/dystopian visual atmosphere accompanied by a electronica soundtrack. Wipeout is the patron saint of futuristic racing games.

Simulation racing games seek to exactly simulate the handling characteristics of a real car. Games like the Gran Turismo series, F355 Challenge and the famous Grand Prix Legends take great pride in the way they have exactly replicated real tracks and the handling of real cars on those tracks. There are actually people who have become real drivers after learning in these games. Gran Turismo popularized the idea that mainstream simulation games should have dozens of realistically rendered sports cars that need to be collected by the player. In Gran Turismo the incentive to race is to collect cars. Today Microsoft’s Forza series and Sony’s Gran Turismo are the kings of mainstream simulation racing.

There is another sub-genre that doesn’t really have an established name that is somewhere between the simulation and arcade styles of handling. I like to call it sim-arcade. The Dreamcast’s Metropolis Street Racer is an early example of this type of game. Codemasters’ Grid and Grid 2 are more recent examples. In sim-arcade racing games you still have to think about your line and braking correctly for the turns but it’s not quite as anal about it as the simulation games. A lot of people confuse this style for the arcade-style because they assume that any game that is not full-on simulation must be arcade style. A good rule of thumb is that if you don’t have to use the brake except to trigger a drift, you’re playing an arcade style racing game. If you have to actually brake for a turn and you’re not playing a sim, it’s probably this sim-arcade style. There can be a arrogance among simulation players that more realistic games are better but I tend to really enjoy the sim-arcade style.

Descending from 1995’s Sega Rally Championship rally racing games are intended to replicate rally driving on off-road surfaces. The actual sport of rally racing takes place as a series of time trials cars drive individually but some of these games allow players to drive against other cars as well. The Sega Rally games take a more arcade approach to handling while Codemasters’ Colin McRae Rally and Dirt games take a more balanced approach somewhere between sim and arcade. Today Dirt 3 and Dirt Showdown basically own this genre.

I wish I could say that the current state of the racing game genre is as rich and vibrant as it was in the past. There is a crunch going on in the videogame industry where game budgets are increasing faster than sales and the large videogame publishers increasingly feel they can’t take risks about what their customers will buy. I suspect that racing games have become labeled risky niche products while military-style first person shooters like Call of Duty and third person action games like Assassin’s Creed are commanding big budget development dollars.

In 2010 when Disney and Activision put out well-advertised arcade-style racing games (Split/Second and Blur, respectively) sales were abysmal and the excellent studios behind those games (Black Rock and Bizarre Creations, respectively) were closed. The fact that both games looked superficially similar, which confused potential customers and the fact that both games were released in the same week up against the blockbuster hit Red Dead Redemption does not seem to have entered any executives minds as to why sales were poor. A chill seemed to descend upon the arcade racing subgenre after that with only Electronic Arts carrying the torch after that with their Need for Speed games.

The videogame playing public, it seems, are sick of just going around in circles and developers can’t seem to figure out what to do next.

Lately developers have been keen to invent shockingly dumb and bizarre plots to justify racing games:

- In Split/Second the game is supposed to be some massive reality TV show where the producers have conveniently rigged and entire abandoned city to explode while daredevils race through it in order to provide interesting television.

- In Driver: San Francisco the main character is actually having a coma dream where he believes he can jump into the consciousnesses of drivers in San Francisco and complete tasks in their cars. I wish I was making this up.

Racing games, like puzzle games, are probably better off without plots.

Still, I think racing games need a kick in the pants in order to stay a relevant mainstream genre.

In other genres, like side-scrolling shooters and platformers the influence of indie developers are helping those genres find the souls they had lost under the weight of big budget design by committee. I’m hoping something similar happens with racing games. I am extremely enthusiastic about the 90s Arcade Racer game on Kickstarter that is a love letter to the arcade racing games that Sega made in the late 1990s (Super GT/SCUD Race and Daytona USA 2) that they were too stubborn to release on consoles.

Sega Saturn

This is my Sega Saturn, which I bought used at The Record Exchange (now simply The Exchange) on Howe Rd. in Cuyahoga Falls in October 1999.

I know this because I saved the date-stamped price tag by sticking it on the Saturn’s battery door.

The Saturn was Sega’s 32-bit game console, a contemporary of the better known Nintendo N64 and the Sony PlayStation. It lived a short, brutish existence where it was pummeled by the PlayStation. In the US the Saturn came out in May 1995 and was basically dead by the end of 1998.

The Saturn was the first game console that I truly loved. Keep in mind that I bought mine after the platform was dead and buried and used game stores were eager to unload most of the games for less than $20. If I had paid $399 for one brand new in 1995 with a $50 copy of Daytona USA I might have different feelings.

The thing that makes the Saturn intensely interesting is how it was simultaneously such a lovable platform and a disaster for Sega. It’s a story about what happens when executives totally misunderstand their market and what happens when you give great developers a limited canvas to make great games with and they do the best they can.

When you look at the Saturn totally out of it’s historical context and just look at on it’s own, it’s a fine piece of gaming hardware. Compared to the Sega CD it replaced the quality of the plastic seems to have been improved. The Saturn is substantial without being outrageously huge. The whole thing was built around a top-loading 2X CD-ROM drive.

It plays audio CDs from an on-screen menu that also supports CD+G discs (mostly for karaoke).

It has a CR2032 battery that backs up internally memory for saving games, accessible behind a door at the rear of the console.

It has a cartridge slot for adding additional RAM and other accessories like GameSharks.

There were several official controllers available for it during it’s lifetime.

The two I own are the this 6 button digital controller:

And the “3D controller” with the analog stick that was packaged with NiGHTS:

You can see the clear family resemblance to the Dreamcast controller.

My Saturn is a bit odd because at some point the screws that hold the top shell to the rest of the console sheared off.

That’s not supposed to happen. All that’s holding the two parts of the Saturn together is the clip on the battery door. Fortunately this gives me an excellent opportunity to show you what the inside of the Saturn looks like:

Despite all of this, my Saturn still works after at least 15 years of service.

I should explain why I was buying a Saturn for $25 at The Record Exchange in 1999. You might say that several decisions by my parents and misguided Sega executives led to that moment.

My parents never bought my brother and I videogames as children. I’m not sure if they thought games were time wasters or wastes of money. Or, it could have just been they didn’t have any philosophical problem with them but they were uncomfortable buying a toy more expensive than $100. Whatever the reason we didn’t have videogames. Considering how many awful games people dropped $50 on in the pre-Internet days when there was so little information about which games were worth buying, I can see their point. I also know now that there were plenty of perfectly good games that were so difficult that you might stop playing in frustration and never get your money’s worth out of them.

Instead, videogames were something I would only see at a friend’s house…and when those moments happened they were magical.

I can’t speak for women of my generation but at least for a lot of males of the so-called “Millennial generation” videogames are to us what Rock ‘n Roll was to the Baby Boomers. They are the cultural innovation that we were the first to grow up with and they define us as a generation. If you’re looking for particular images that define a generation and I say to you “Jimi Hendrix at Woodstock” you think Baby Boomers. If I say to you “Super Mario Bros.” you think Millennials.

By 1996 or so I was pretty interested in buying some sort of videogame console, but I was somewhat restricted in what I could afford. The first game system I bought was a used original Game Boy in 1996. However, shortly after that my family got a current PC and my interests shifted to computer games: Doom, Quake, etc, which is what eventually led to the Voodoo 2.

By 1998 I noticed how dirt cheap the Sega Genesis had become so my brother and I chipped in together to buy a used Genesis (which I believe we bought from The Record Exchange). I quickly found that I did enjoy playing 2D games but I was really enjoying the 3D games I was playing on PC.

Sega did an oddly consistent job of porting their console games to PC in the 1990s, so I had played PC versions of some of the games that came out on Saturn in the 1995-1998 timeframe including the somewhat middling PC port of Daytona USA

So in 1999 when I came across this used Saturn for a mere $25 at The Record Exchange, I was eager to buy it.

But why was the Saturn $25 when a used PlayStation or N64 was most likely going for $80-$100 at the same time?

As I noted in the Sega Genesis Nomad post, Sega was making some very strange decisions about hardware in the mid-1990s. At that time Sega was at at the forefront of arcade game technology. Recall that in the Voodoo 2 post I said that if you sat down at one of Sega’s Daytona USA or Virtua Fighter 2 machines in 1995 you were basically treated to the most gorgeous videogame experience money could by at the time. That’s because Sega was working with Lockheed Martin to use 3D graphics hardware from flight simulators in arcade machines.

At the same time as they were redefining arcade games Sega was busy designing the home console that would succeed the popular Genesis (aka the console people refer to today as simply “the Sega”). Home consoles were still firmly rooted in 2D, but there were cracks appearing. For example, Nintendo’s Star Fox for the Super Nintendo embedded a primitive 3D graphics chip in the cartridge and introduced a lot of home console gamers to 3D, one slowly rendered frame at a time. Sega pulled a similar trick with the Genesis port of Virtua Racing, which embedded a special DSP chip in the cartridge (you may remember this from the Nomad post):

Sega decided on a design for the Saturn which would produce excellent 2D graphics with 3D graphics as a secondary capability. The way the Saturn produced 3D was a bit complicated but basically it could take a sprite and position it in 3D space in such a way that it acted like a polygon in 3D graphics. If you place enough of these sprites on the screen you can create a whole 3D scene.

I can see in retrospect how this made sense to Sega’s executives. People like 2D games, so let’s make a great 2D machine. They also must have considered that 3D hardware on the same level as their arcade hardware was not feasible in a $400 home console.

However, Sega’s competitors didn’t see things that way. Sony and Nintendo both built the best 3D machines they could, 2D be damned. One would expect their did this largely in response to the popularity of Sega’s 3D arcade games.

The story that’s gone around about Sega’s reaction to this is that in response they decided to put a second CPU in the Saturn. I have no idea if that’s why the Saturn ended up with two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs, but it would make sense if was an act of desperation.

Having two CPUs is one of those things that sounds great but in reality can turn into a real mess. A CPU is only as fast as the rest of the machine can feed it things to do. If say, one CPU is reading from the RAM and the other can’t at the same time, it sits there idle, waiting. There are also not that many kinds types of work that can easily be spread across two CPUs without some loss in efficiency. If the work one CPU is doing depends on work the other CPU is still working on the first CPU sits there idle, waiting. These are problems in computer science that people are still working furiously on today. These were not problems Sega was going to solve for a rushed videogame console launch 19 years ago.

The design they ended up with for the Saturn was immensely complicated. All told, it contained:

- Two Hitachi SH-2 CPUs

- One graphics processor for sprites and polygons (VDP1)

- One graphics processor for background scrolling (VDP2)

- One Hitachi SH-1 CPU for CD-ROM I/O processing

- One Motorola 68000 derived CPU as the sound controller

- One Yamaha FH1 sound DSP

- Apparently there was another custom DSP chip to assist for 3D geometry processing

That’s a lot of silicon. It was expensive to manufacturer and difficult to program. The PlayStation, which started life at $299, had a single CPU and a single graphics processor and in general produced better results than the Saturn.

Sega had psyched itself out. Here the company that was showing everyone what brilliant 3D arcade games looked like failed to understand that they had actually fundamentally changed consumer expectations and built a game console to win the last war, so to speak.

When the PlayStation and N64 arrived they ushered in games that were built around 3D graphics. Super Mario 64, in particular made consumers expect increasingly rich 3D worlds, exactly the type of thing the Saturn did not excel at.

Sega had gambled on consumers being interested in the types of games they produced for the arcades: Games that were short but required hours of practice to master. By 1997-1998 consumers’ tastes had changed and they were enjoying games like Gran Turismo that still required hours to master but offered hours of content as well. 1995’s Sega Rally only contained four tracks and three cars. 1998’s Gran Turismo had 178 cars on 11 tracks.

Sega’s development teams eventually adapted to this new reality but it was too late to save the doomed Saturn. Brilliant end-stage Saturn games like Panzer Dragoon Saga and Burning Rangers would never reach enough players’ hands to make a difference.

For the eagle eyed…This is a US copy of Burning Rangers with a jewel case insert printed from a scan of the Japanese box art.

By Fall-1999 the Saturn was dead and buried as a game platform. Not only had it failed in the marketplace but it’s hurried successor, the Dreamcast, was now on store shelves. That’s why a used Saturn was $25 in 1999.

The thing was that despite the fact that the Saturn had failed, the games weren’t bad, and since I was buying them after the fact they were dirt cheap. I accumulated quite a few of them:

Oddly enough, my favorite Saturn game was the much criticized Saturn version of Daytona USA that launched with the Saturn in 1995.

The original Saturn version of Daytona USA was a mess. Sega’s AM2 team, who had developed the original arcade game had been tasked with somehow creating a viable Saturn version of Daytona USA. The whole point of the game was that you were racing against a large number of opponents (up to 40 on one track). The Saturn could barely do 3D and here it was being asked to do the impossible.

The game they produced was clearly a rushed, sloppy mess. But it was still fun! The way the car controls is still brilliant even if the graphics can barely keep up. I fell in love with Daytona. Later Sega attempted several other versions of Daytona on Saturn and Dreamcast but I vastly prefer the original Saturn version, imperfect as it may be.

Another memorable game was Wipeout. To be honest, when I asked to see what Wipeout was one day at Funcoland I had no idea that the game was a futuristic racing game. I thought it had something to do with snowboarding!

Wipeout was a revelation. Sega’s games were bright and colorful with similarly cheerful, jazzy music. Wipeout is a dark and foreboding combat racing game that takes place in a cyberpunk-ish corporate dominated future. I still catch myself humming the game’s European electronica soundtrack. The game used CD audio for the soundtrack so you could put the disc in a CD player and listen to the music separately if you wished. Wipeout was the best of what videogames had to offer in 1995: astonishing 3D visuals and CD quality sound.

From about 1999 to 2000 I had an immense amount of fun collecting cheap used Saturn classics like NiGHTS, Virtua Cop, Panzer Dragoon, Sonic R, Virtua Fighter 2, Sega Rally, and others…As odd as this is to say, the Saturn was my console videogame alma mater.

Today I understand that something can be a business failure but not a failure to the people who enjoyed it. To me, the Saturn was a glorious success and I treasure the time I have had with it.

3DFX Voodoo2 V2 1000 PCI

This is a 3DFX Voodoo 2 V2 1000 PCI still sealed in the box.

I actually own three Voodoo 2’s. The first one is a Metabyte Wicked 3D (below, with the blue colored VGA port) that I bought from a friend in high school. The second one is the new-in-box 3DFX branded Voodoo 2 I bought off of ShopGoodwill last year. The third one (below, with the oddly angled middle chip) is a Guilliemot Maxi Gamer 3D2 I bought at the Cuyahoga Falls Hamfest earlier this year.

The Voodoo 2, in all of its manifestations, is my favorite expansion board of all time. It’s one of the last 3D graphics boards that normally operated without a heatsink so you can gaze upon the bare ceramic chip packages and the lovely 3DFX logos emblazoned upon them. It was also pretty much the last 3D graphics board where the various functions of the rendering pipeline were still broken out into three separate chips (two texture mapping units and a frame buffer). The way the three chips are laid out in a triangle is like watching jet fighters flying in formation.

It’s hard to explain to someone who wasn’t playing PC games in the late-1990s what having a 3DFX board meant. It was like having a lightswitch that made all of the games look much, much better. There are perhaps three tech experiences that have utterly blown my mind. One of them was seeing DVD for the first time. Another is seeing HDTV for the first time. Seeing hardware accelerated PC games on a Voodoo 2 was on the same level.

A friend of mine in high school won the Metabyte Wicked 3D in an online contest. I remember the day it arrived at his house I had walked home from school trudging up and down piles of snow that had been piled up on the sidewalk to clear the roads and I got home exhausted…And he calls me asking if I wanted to come over as he installed the Voodoo 2 card and fired up some games. Even though I was exhausted I eagerly accepted.

I think I saw hardware accelerated Quake 2 that day…Nothing else would ever be the same. I was immensely jealous.

Ever since personal computers have been connected to monitors there has been some sort of display hardware in a computer that output video signals. Often times this hardware included capabilities that enhanced or took over some of the CPU’s role in creating graphics.

When we talk about 2D graphics we mean graphics where for the most part the machine is copying an image from one place in the computer’s memory and putting int another place in the computer’s memory. For example, if you imagine a scene from say, Super Mario Bros. the background is made up of pre-prepared blocks of pixels (ever notice how the clouds and the shrubs are the same pattern or pixels with a color shift?) and Mario and the bad guys are each particular frame in a short animation called a sprite. These pieces of images are combined together in a special type of memory that is connected to a chip that sends the final picture to the TV screen or monitor.

It’s sort of like someone making one of those collages where you cut images out of a magazine and paste them on a poster-board. The key to speeding up 2D graphics in a computer is speeding up the process of copying all of the pieces of the image to the special memory where they need to end up. You might have heard about the special “blitter” chips in some Atari consoles and the famous Amiga computers that made their graphics so great. 2D graphics were ideal for the computing power of the time but they give videogame designers limited ability to show depth and perspective in videogames.

Outside of flight simulator games and the odd game like Hard Drivin and Indy 500 almost all videogames used 2D graphics until the mid-1990s. PC games during the 2D graphics era were mostly being driven by the CPU. If you bought a faster CPU, the games got more fluid. There were special graphics boards you could buy to make games run faster, but the CPU was the main factor in game performance.

Beginning in about 1995-1996 there was a big switch to 3D graphics in videogames (which is totally different than the thing where you wear glasses and things pop out of the screen…that’s stereoscopics) and that totally changed how the graphics were being created by the computer. In 3D graphics the images are represented in the computer by a wireframe model of polygons that make up a scene and the objects in it. Special image files called textures represent what the surfaces of the objects should look like. Rendering is the process of combing all of these elements to create an image that is sent to the screen. The trick is that the computer can rotate the wireframe freely in 3D space and then place the textures on the model so that they look correct from the perspective of the viewer, hence “3D”. You can imagine it as being somewhat akin to making a diorama.

With 3D graphics videogame designers gained the same visual abilities as film directors: Assuming the computer could draw a scene they could place the player’s perspective anywhere they desired.

The problem with 3D graphics is that they are much more taxing computationally than 2D graphics. They taxed even the fastest CPUs of the era.

In 1995-1996 when the first generation of 3D games started appearing in PCs they looked like pixelated messes on a normal computer. You could only play them at about 320×240, objects like walls in the games would get pixelated very badly when you got close to them, and the frame rate was a jerky 20 fps if you were lucky. Games had started using 3D graphics and as a result required the PC’s CPU to do much, much more work than previous games. When Quake, one of the first mega-hit 3D graphics-based first person shooters came out it basically obsoleted the 486 overnight because it was built around the Pentium’s floating-point (read: math) capabilities. But even then you were playing it at 320×240.

At the same time arcade games has been demonstrating much better looking 3D graphics. When you sat down in front on an arcade machine like Daytona USA or Virtua Fighter 2 what you saw was fluid motion and crisp visuals that clearly looked better than what your PC was doing at home. That’s because they had dedicated hardware for producing 3D graphics that took some types of work away from the CPU. These types of chips were also used in flight simulators and they were known to be insanely expensive. However, by the time the N64 came out in 1996 this type of hardware was starting to make it’s way into homes. What PCs needed was their own dedicated 3D graphics hardware. They needed hardware acceleration.

That’s what the Voodoo 2 is. The Voodoo 1 and it’s successor the Voodoo 2 were 3DFX’s arcade-quality 3D graphics products for consumer use.

A texture mapping unit (the two upper chips labeled 3DFX on the Voodoo 2) takes the textures from the memory on the graphics board (many of those smaller rectangular chips on the Voodoo 2) and places them on the wireframe polygons with the correct scaling and distance. The textures may also be “lit” where the colors of pixels may be changed to reflect the presence of one or more lights in the scene. A framebuffer processor (the lower chip labeled 3DFX) takes the 3D scene with the texture and produces a 2D image that is built up in the framebuffer memory (the rest of those smaller, rectangular chips in the Voodoo 2) that can be sent to the monitor via the RAMDAC chip (like a D/A converter for video, it is labeled GENDAC on the Voodoo 2).

3DFX was the first company to produce really great 3D graphics chips for consumer consumption in PCs. Their first consumer product was the Voodoo 1 in late 1996. It was soon followed in 1998 by the Voodoo 2.

The Voodoo 2 is a PCI add-in board that does not replace the PC’s 2D graphics card. Instead, there’s a cable that goes from the 2D board to the Voodoo 2 and then the Voodoo 2 connectors to the monitor. This meant that the Voodoo 2 could not display 3D in a window, but what you really want it for is playing full-screen games, so it’s not much of a loss.

My friend who won the Metabyte Wicked 3D card later bought a Voodoo 3 card and sold me the Voodoo 2 sometime in 1999.

I finally had hardware acceleration. At the time we had a Compaq Presario that had begun life has a Pentium 100 and had been upgraded with an Overdrive processor to a Pentium MMX 200. It was getting a bit long in the tooth by this time, which was probably 1999. Previously I had made the mistake of buying a Matrox Mystique card with the hope of it improving how games looked and being bitterly disappointed in the results.

Having been a big fan of id Software’s Doom I had paid full price ($50) for their follow-up game Quake after having played the generous (quarter of the game) demo over and over again. Quake was by far my favorite game (and it’s still in my top 5).

id had known that Quake could look much better if it supported hardware acceleration. They had become frustrated with the way that the needed to modify Quake in order to support each brand of 3D card. Basically, the game needs to instruct the card on what it needs to do and each of card used a different set of commands. id had decided to create their own set of commands (called a miniGL because it was a subset of SGI’s OpenGL API) in the hope that 3D card makers would supply a library that would convert the miniGL commands into commands for their card. The version of Quake they created to use the miniGL was called GLQuake and it was available as a freely downloadable add-on.

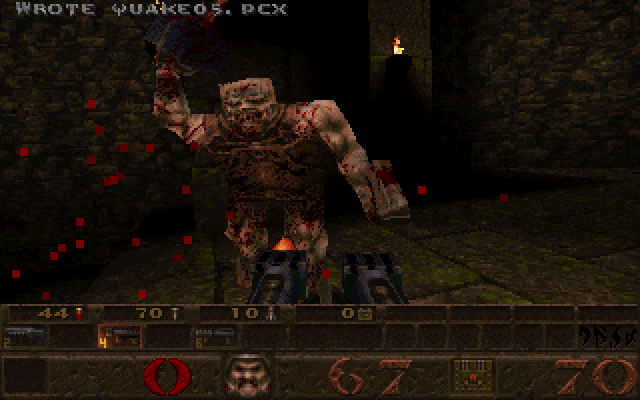

It’s a little hard to show you this today, but this is what GLQuake (and the Voodoo 2) did for Quake. First, a screenshot of Quake without hardware acceleration (taken on from the Pentium III with a Voodoo 3 3000):

Pixels everywhere.

Now, with hardware accelerated GLQuake:

Suddenly the walls and floor look smooth and not blocky. Everything is much higher resolution. In motion everything is much fluid. It may seem underwhelming now, but this was very hot stuff in 1997 and blew me away when I first saw in 1999.

What we didn’t realize at the time was that it was pretty much all downhill for 3DFX after the Voodoo 2. After the Voodoo 2 3DFX decided to stop selling chips to 3rd party OEMs like Metabyte and Guilliemot and produce their own cards. That’s why my boxed board is just branded 3DFX. This turned out to be disastrous because suddenly they were competing with the very companies that had sold their very successful products in the 1996-1998 period. They also released the Voodoo 3, which combined 2D graphics hardware with 3D graphics hardware on a single chip (that was hidden under a heatsink).

The Voodoo 3 was an excellent card and I loved the Voodoo 3 3000 that was in the Dell Pentium III my parents bought to succeed the Presario. However, 3DFX was having to make excuses for features that the Voodoo 3 didn’t have and their competitors did have (namely 32-bit color). Nvidia’s TNT2 Ultra suddenly looked like a better card than the Voodoo 3.

3DFX was having trouble producing their successor to the Voodoo line and instead was having to adapt the old Voodoo technology to keep up. The Voodoo 4 and 5, which consisted of several updated Voodoo 3 chips working together on a single board ended up getting plastered by Nvidia’s GeForce 2 and finally GeForce 3 chips which accelerated even more parts of the graphics rendering process than 3DFX did. 3DFX ceased to exist by the end of 2000. Supposedly prototypes of “Rampage”, the successor to Voodoo were sitting on a workbench being debugged the day the company folded.

Back in the late-1990s 3D acceleration was a luxury meant for playing games. Today, that’s no longer true: 3D graphics hardware is an integral part of almost every computer.. Today every PC, every tablet, and every smartphone sold has some sort of 3D acceleration. 3DFX showed us the way.

Sega Genesis Nomad

This is my Sega Nomad, the portable version of the venerable Sega Genesis videogame console, introduced in 1995. I don’t remember which thrift store I found it at, but it’s likely to have been the old State Road Goodwill, sometime in the early 2000s.

The Genesis is better known as “the Sega” (as in, “remember when were were kids and played Sega at your house?”) than by it’s real name. It was Sega’s one and only true hardware success.

By the end of the 1980s through a combination of quality first party games and tight control of third party publishers Nintendo had come to dominate the home videogame console market. The Genesis broke Nintendo’s near monopoly and setup the first great “console war” of the 1990s. Powered by the venerable Motorola 68000 CPU (which also powered the Apple Macintosh and is one of the great CPUs of all time) the Genesis was home to Sonic the Hedgehog, edgy fighting games, and popular sports games.

While they were riding high on the success of the Genesis in the early to mid 1990s Sega made some bizarre decisions about videogame hardware that damaged their relationship with consumers in the years to follow.

There are a lot of companies that you come to find out 20 years later had design concepts or prototypes for ideas that seemed really cool but in retrospect were probably best left on the drawing board. These drawings for Atari computers that never were and these Apple prototype designs come to mind. There are probably sound reasons why these things were never produced for sale. In Sega’s case, they actually produced some of their bizarre ideas and basically every one of them was either an embarrassing failure or was received with apathy by the public.

When you consider the numbers of consoles and hardware add-ons for consoles that Sega either produced or licensed to other companies it’s staggering to think how much hardware they produced in such short a time between 1991 and 1995:

- There were two versions of the Sega CD that added better graphics and a CD-ROM to the Genesis.

- The Sega CDX that combined the Genesis and the Sega CD into one semi-portable console.

- The Sega 32X add-on for the Genesis that added somewhat pathetic 32-bit CPUs to extend the Genesis’s lifespan.

- An attachment for the Pioneer LaserActive that combined Genesis and Sega CD hardware with a LaserDisc player.

- The JVC X’Eye that was a combination Genesis and Sega CD console licensed to JVC.

- The Sega TeraDrive that somewhat unbelievably combined an 286-based PC and a Genesis.

The Nomad is another one of these bizarre hardware ideas. The technology of 1995 could not provide the Nomad with a crisp screen, a manageable size, or anything that could be considered better than horrendous battery life.

Here’s the back of the Nomad. Notice there is no battery compartment but there are contacts for a battery accessory. You were expected to attach an external battery pack to the back of the Nomad to actually use it as a portable game system. Without the pack, the Nomad is already over 1.5 inches thick on it’s “thin” edge. I don’t have a battery pack so I can’t speak directly to what the weight and battery life are like with the pack installed, but you read phrases like “the low battery light told you when the Nomad was on” and “horrendous” to describe the battery life.

The Nomad’s screen, while much better at producing color at the Casio TV-1000 I blogged about in February, has some serious issues with ghosting. As you can imagine, this is an issue with games like Sonic the Hedgehog that have fast movement.

Oddly, the blurring actually does a good job at hiding the awful color dithering in Virtua Racing.

Apparently part of the cause of the Nomad’s notoriously poor battery life is the high voltage florescent backlight which also lights the screen in an uneven way.

If you had paid $180 for a Nomad in 1995 expecting a portable Genesis as advertised, you would have cause to be unhappy. In that respect, the Nomad was a failure.

The thing is though, is that if you just consider the Nomad to be a miniature, self-contained Genesis model, it’s pretty fantastic. The saving grace of the Nomad is that it has everything a Genesis has: An AV output, a second controller port, and a six button controller. I have several Genesis controllers and I dislike all of them. The buttons feel clunky and the D-pads feel mushy. The Nomad’s controls seem much sharper. I like the smooth, convex buttons on the Nomad much better than the rough, concave buttons on most Genesis controllers.

Now, you can’t use the Nomad with the 32X (because the AV output that’s necessary to connect to the 32X is covered up by the bulk of the 32X) or the Sega CD (because the Nomad lacks the necessary expansion port) but in all other respects it IS a Genesis. It uses the same AV cables and the same power brick as the Genesis Mark 2 model. If you want to collect Genesis cartridges and play them on a real Genesis but you lack space for a real Genesis in your residence, the Nomad is for you. You would do yourself a favor though, by plugging it into a TV (especially a late-model CRT TV).

One problem the Nomad shares with the Genesis Mark 2 is that the connection between the power input and the PCB board can become weakened causing the Nomad to randomly shut off or not turn on at all. My Nomad had this problem until my father opened up the unit and re-solderer the power input’s connection to the PCB. One of the five screws on the back of the unit is a security screw, so safely cut that screw post, which does not affect the structure of the case at all.

If you really, really want to use the Nomad as a portable Genesis there are mods available to help. One mod replaces the florescent backlight with an LED for significantly improved battery life but otherwise stock appearance. Another mod replaces the mid-90s vintage LCD with a modern LCD for improved screen clarity.

Nintendo Game Boy Micro

I had originally planned to put up a different post this week but some technical issues and the fact that I had a cold means that post will have to wait for some other week.

Today though, I’m going to bend the rules somewhat because this is an item that technically I didn’t buy at a thrift store but I did buy used.

This is my Nintendo Game Boy Micro which I purchased sometime in 2008 at The Exchange in Cuyahoga Falls.

Released in 2005, the Game Boy Micro is a miniaturized Game Boy Advance that loses compatibility with original Game Boy and Game Boy Color games but gained a brilliant (if tiny) screen and a headphone jack that the Game Boy Advance SP oddly lacked..

The Game Boy Micro is, in my opinion, the sexiest piece of videogame hardware ever created. It’s so tiny and jewel-like while at the same time so utterly minimalistic that it just looks better than anything else Nintendo, or perhaps anyone making portable game systems has ever made. It’s not surprising looking at it’s brushed metal construction that the Micro was a contemporary of the iPod Mini and was widely believed to be Nintendo’s bid to capture customers looking for another stylish portable gizmo. It’s so beautiful that you almost feel bad inserting a cartridge because it clashes with the color scheme.

Practially the Micro can be a bit tough to hold for any long period of time. The tiny size (it only measures 50×101×17.2 mm) means that in order to have your index fingers on the shoulder buttons and your thumbs on the D-pad and a+b buttons there’s a good chance you’ll have to hold your hands at an uncomfortable angle. I have pretty small hands and holding the Micro is just about at the edge of discomfort for me. Additionally, while the screen is bright and the colors are well defined the screen is still just 2 inches wide.

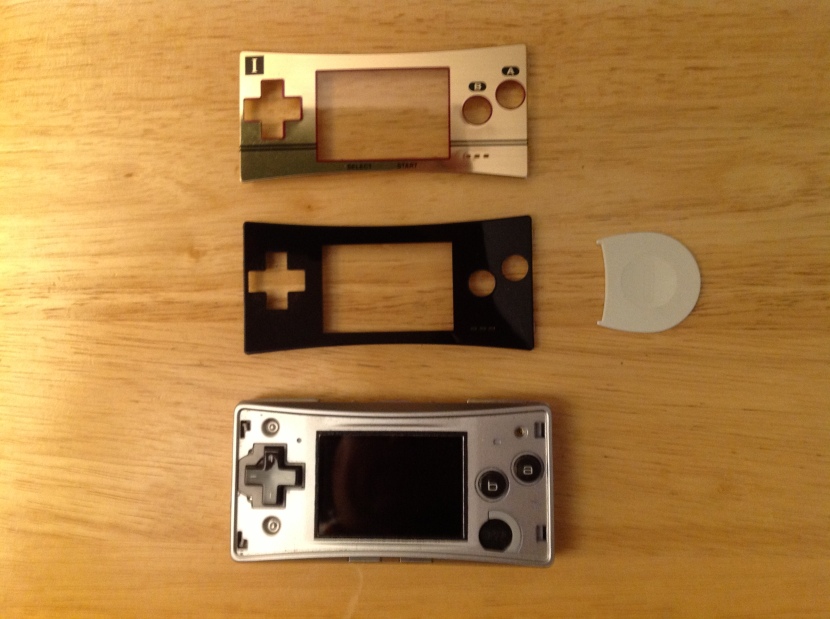

The Micro’s party piece is that it’s faceplates are removable so you can change the appearance of the system by changing faceplates with a plastic tool.

Here are the three faceplates I own, along with the plastic tool:

I believe that when I bought the Micro used it was wearing the obnoxious red/orange faceplate. Back in 2008 you could still order new faceplates from Nintendo’s parts site so I bought the stylish black plate and the nostalgic Famicom faceplate. Sadly today they only offer replacement AC-adaptors.

The plastic tool inserts into these two holes on the side of the Micro with the D-pad (on either side of the screw):

Micro owner Pro-tip: Always insert new faceplates so that you hook in the side with the longer hooks near the a+b buttons first.

This is what the Micro looks like without any faceplate mounted:

One practical advantage to the faceplates is that they act as hard screen protectors, but really they just look bitch’n cool.

However, the real reason I want to talk about the Game Boy Micro is it’s historical significance to Nintendo. The Game Boy Micro is the last Game Boy as well as the last 2D gaming system from Nintendo.

Now, I would not be shocked if some day Nintendo reuses the Game Boy name but suffice to say Nintendo started selling a line of cartridge-based portable game systems with four face buttons (labeled a, b, start, and select), a D-pad, and one screen in 1989 with the original Game Boy and created a succession of systems with those attributes that ended in 2005 with the Game Boy Micro.

Following the Game Boy Micro Nintendo retired the Game Boy name and has produced the Nintendo DS line of cartridge-based portable game systems with two screens, one of which is a stylus-based resistive touchscreen, six face buttons (labeled a, b, x, y, start, and select), and (at least) a D-pad.

More importantly though, the Game Boy Micro was the last Nintendo system of any kind that was primarily built to play games based on 2D, sprite-based graphics rather than today’s 3D, polygon-based graphics.

This means that the Game Boy Micro was Nintendo’s final love letter to the era when it dominated the videogame world with the NES/Famicom and SuperNES/Super Famicom. There’s no coincidence to the fact that the Micro itself resembles and NES/Famicom controller.

From the release of the Famicom in 1983 to December 3rd, 1994 (when Sony released the Playstation in Japan) Nintendo was undoubtedly the single most important force in the console videogame world. Surely Sega played some part as well, but while they could on occasion be Nintendo’s equal they were never Nintendo’s superior.

But, as the world marveled at the Playstation and the rise of 3D graphics, Nintendo’s influence crested and then began to wane. Today they are an important part of the industry, but they have never again become undisputed champion.

However, in the portable gaming arena, Nintendo was still the undisputed champion (and still is today, as tough as it is for this PSP and Vita owner to admit). When Nintendo decided to replace the Game Boy Color in 2001 it returned to a 2D-based system and created the Game Boy Advance. An era of 2D nostalgia reigned with the GBA finding itself home to classics of the 16-bit era re-released as GBA games and new 2D classics that heavily drew inspiration from SNES games.

So, when Nintendo said it’s final goodbye in 2005 with the Game Boy Micro it was really closing the door on the era of 2D gaming it had dominated from 1983 to 2005. In that way the Micro is comparable to the last tube-based Zenith Transoceanic or the last piston-engined Grumman fighter aircraft. When a great company wants to say goodbye to one of it’s great products they will often create something fantastic as a last hurrah and that is clearly what Nintendo did with the Game Boy Micro.